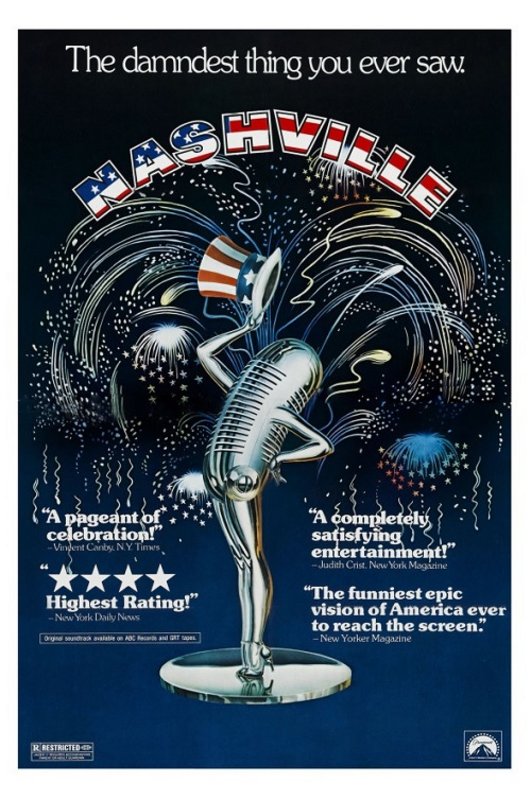

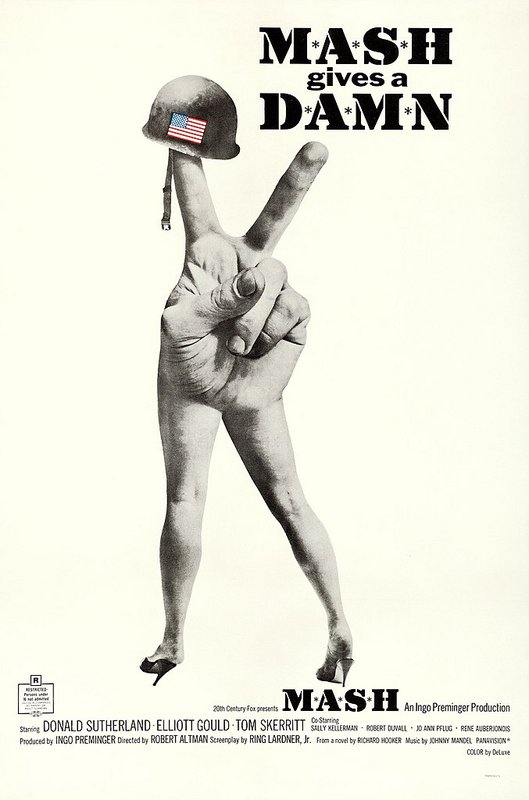

MASH - 1970

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Ring Lardner Jr.

Based on a novel by Richard Hooker

Starring Donald Sutherland, Elliott Gould, Tom Skerritt

Sally Kellerman & Robert Duvall

Like many people, I grew up getting to know

M*A*S*H as a television show that regularly haunted weekday evenings with a never ending series of reruns, specials and spin-offs. Nobody ever stopped to inform me that it had originally started life as a novel, which was adapted to the big screen, marking Robert Altman's breakthrough in feature films - lastly transmogrifying into the series I was so used to. Even the fact that my parents saw it on the big screen when they were courting was never assumed to be information worthy of passing on to me. It's a film that I had to slowly work my way into, because Alan Alda and company really clouded my ability to just take it on as a lone entity - I happened not to be a huge fan of that show, which unfortunately gave me preconceptions I took into the film. Robert Altman's attempt to make films that weren't mutated into soulless commercial product, and turn

MASH into a scolding yet funny antiwar feature which highlighted the madness and crass obscenity of war, wasn't initially as clear as it should have been.

The film begins by introducing us to Capt. Benjamin Franklin "Hawkeye" Pierce Jr. (Donald Sutherland) as he arrives to take on duty at a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital during the Korean War. He immediately meets Capt. Augustus Bedford "Duke" Forrest (Tom Skerritt) and steals a jeep to take him to where they'll be operating on young war casualties. The two come across a taciturn, misanthropic fellow-surgeon Major Frank Burns (Robert Duvall) whose focus on being religiously pious seems to be hypocritical in view of some of his behaviour - so when Major Margaret Houlihan arrives as Head Nurse and the two become intimately acquainted both Hawkeye and Duke make sure they push Burns to the point where he breaks - and is carted away in a straight-jacket. In the meantime Capt. John Francis Xavier "Trapper John" McIntyre (Elliott Gould) arrives, and the three doctors play pranks and are involved in escapades that mostly go to show the lengths these surgeons take to alleviate the horrors of the situations they face in their operating tent. The film follows them and strides forth in an episodic nature, with the emphasis on humour and light-hearted rebellion against authority.

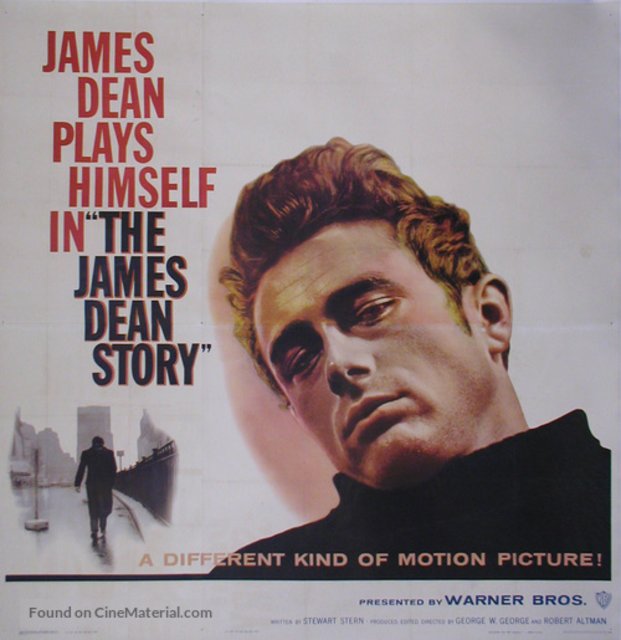

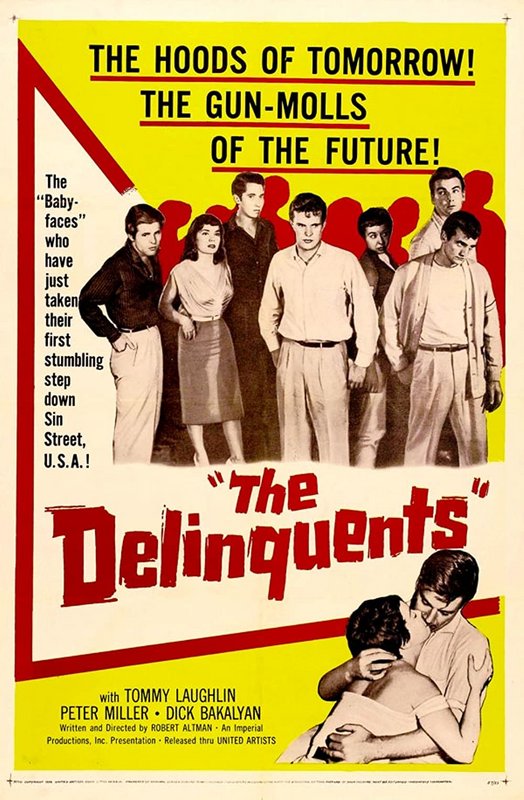

By the time he was offered the chance to direct

MASH, Robert Altman had been in the business for a considerable amount of time, had spent 10 years doing television work and had directed 4 features - he was the ultimate experienced novice, and was well aware of what studios could do after his experiences directing

Countdown. Many more experienced directors had already been offered the screenplay, and rejected it - but the spirit of anarchy it represented must have made the film very attractive to such a maverick. Producer Ingo Preminger met with the renegade director, and Altman, for his part, showed him the short film he'd made some time earlier in '67 -

Pot au feu which amused and encouraged Preminger enough to give the job to him. From that moment on, Altman carefully set out to attract as little attention as he could so that he could have the freedom to do the film his way (bringing the film in under-budget and on time) - in a manner that was fairly revolutionary in those days. Ad-libbing from the cast was encouraged, and actors could speak over each other's lines with creative freedom - the camera itself having a likewise freedom to catch incidental moments. Stars Elliott Gould and Donald Sutherland thought Altman was mad, and at many stages tried to get him fired - fearing the resulting film would ruin their reputation.

The emergent film plays a little rough today, for although much of the misogyny and racism had been scaled back from the novel, it still chafes a little to watch what these doctors do. Altman defends this by saying he intentionally had his characters do these bad things so what they did could be compared to the carnage going on during a war - explicitly demonstrating just how obscene and awful war really is. Worse than any kind of sexism, racism or crude behaviour you can imagine. The film's only black character is called "spearchucker" and the women in the film are treated purely as sexual objects, their work as nurses receding into the background. In a situation like that, it's more difficult to lighten my mood to the point where I'd laugh at their antics - but at the same time I still appreciate the illumination all of this does. The naturalism of the actors also helps the film a great deal, and instantly date any other film (war film or otherwise) from the year

MASH was released - while

MASH itself doesn't seem dated at all. Like

Apocalypse Now would at the end of the decade, this film was a direct illustration of the insanity of war - something Altman came to realise more and more as the production continued.

Screenwriter Ring Lardner Jr. initially felt burned by Altman's process and what that had done to his screenplay. Most of the dialogue from it had been completely transformed - to the point where he complained that "not one word" he'd written had managed to make it to the screen. Compounding this was the irony of him winning an Oscar for his screenplay for

MASH. Over the years people (including a conciliatory Lardner Jr. himself) have argued that the basic structure and story remained very much intact, and that some dialogue had indeed made it into the finished product. At first glance it might seem like an undeserved Oscar win, but on closer examination it seems less so. The film also managed to garner an Oscar nomination for Robert Altman himself - a dizzying achievement when you consider just how abused and mistreated he'd been by studios and critics for his work (his previous film,

That Cold Day in the Park deserved far more recognition.) The film's box office success, coupled with those nominations assured that

MASH would be nominated for Best Picture at the 1971 Academy Awards - but it ended up losing to another war film 20th Century Fox had made,

Patton, and Altman likewise lost to Franklin J. Schaffner who directed that film.

Altman dragged cinematographer Harold E. Stine along with him to be cinematographer on this film - he knew him from his days directing television, and The D.P. was up to speed with Altman's fast-paced style. Stine would need to keep up with that pace and almost had to be as improvisational as the actors were. Those praising the inventiveness of many of the shots wouldn't have been fully aware just how improvised many of them were. Visually, the muddy brown and verdant greens dominate the film to the extent that when Hawkeye and Trapper John put on golfing clothes the burst of colour is shocking and incongruent to the entire film. Of course, the surgical scenes have their fair share of many different toned reds - and were lucky to escape the cutting room floor. Stine would soon be nominated for an Oscar for his work on

The Poseidon Adventure, but missed out here. It's a good-looking film, and I'd say the cinematography is a definite success. More egg on the face of 20th Century Fox who at first demanded that Harold E. Stine not be used on the film - but Altman was adamant, because he knew Stine was a director of photography who would do what he wanted.

Scoring the film was Johnny Mandel, who had worked on Altman's previous film

That Cold Day in the Park. It's Mandel who composed the tune of the now famous "Suicide is Painless", with Altman's son Mike Altman who was only a teenager at the time (around 13 or 14) - the director only wanted some cheap, improvised lyrics and everywhere he turned he got greater lyrics than he really wanted for this seemingly invented song. The most interesting result from this is that Robert Altman's young son ended up earning millions of dollars from the royalties from that song while the director himself only ever earned $75 grand for directing the film. Mandel also found various Japanese songs to use during radio and loudspeaker moments (usually better than the "bad ones" Altman was really looking for.) These musical interludes, including sung songs and various other tunes make up the eclectic sound of the film - giving a kind of army-regulated radio feel to everything that happens. Mandel had been an Oscar winner for the song "The Shadow of Your Smile" in 1966 but overlooked for a nomination when it came to "Suicide is Painless" - which is strange considering just how big the song became.

Forbidden Planet's art director, Arthur Lonergan, was officially an art director for

MASH, but Robert Altman recalls that Leon Eriksen was the man responsible for the art direction in this film. Eriksen was non-union, and so in the credits he's an "associate producer" - thus escaping any of the official ramifications he would have had being officially credited for the job he did. If you check out his credits on the IMDb, you'll see he's always an art director or production designer except for this one "associate producer" credit. It's another crew member Altman carried over from

That Cold Day in the Park and an innovator over how dirty he made the costumes and set decoration look - not to mention the ways he coloured and created blood for the operating scenes. This immediately made

MASH look better and much more realistic than other 20th Century Fox war films being produced at the same time like

Patton (which, ironically won the Oscar for Best Art Direction-Set Decoration - go figure) and

Tora! Tora! Tora! Perhaps the Academy had the last laugh there, for Eriksen couldn't be nominated at all due to his union predicament. He did a great job on

MASH though.

Sally Kellerman is great in the film, and although it's

very much an ensemble movie she was the lone Oscar nominee acting-wise, beaten by the elderly Helen Hayes for her comedic moments as the old biddy Ada in

Airport for Best Supporting Actress, but neither should have won. The award should have gone to Karen Black for her amazing performance in

Five Easy Pieces. Editor Danford B. Greene did a marvelous job as well, and received a deserved Oscar nomination. He was beaten by Hugh S. Fowler and his fancied work on the favoured film at Oscar time,

Patton. In any case, you have to take into account the fact that Altman was along for the ride in the editing suite, and had significant say over the direction it took - not that 20th Century Fox would have been very pleased about that. The studio kept on insisting on changes that would have dampened the film's impact and made it just your average run-of-the-mill comedy. They wanted the bloody operating theatre scenes gone, bad language out, and various other cuts and adjustments. The pace of the film and cuts from the action just as something funny has occurred are part of it's grace - and editing should not be subject to the demands of non-artists or non-professionals.

That Cold Day in the Park was a

great film - but

MASH was the first film that Robert Altman practiced and experimented with, creating a new style - one that would come to be associated with his films. If you watch the movie closely, you'll notice that there is as much going on in the background as there is in the foreground - and that if you alter your perspective you notice actions that you completely missed the first few times you watch the film. Altman also created an 8-track system for audio, then a 16 track system, because he wanted to record more than the principals. The feel the film gets is something approaching real life - where people rarely stand still and stay quiet while other people command an imaginary audience. Altman had been locked out of the studio in the past for even daring to attempt a scene where two people talk over each other, but in

MASH he doggedly tried this again, and it became something of a signature. Not only did it come off, but he had the last laugh when

MASH became the third-highest grossing film of the year and a critical success on top of that. The film won the prestigious Palme d'Or at Cannes, won the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture - Comedy or Musical - with Robert Altman himself winning a Kansas City Film Critics Circle Award. He'd arrived, and would finally have enough clout to make films he wanted,

the way he wanted.

I really like and admire this film, and find parts of it really funny - though perhaps not as funny as other people find it. I like it more for it's style, thematic meaning and merit than the comedy. I do appreciate the "hot lips" moment, and the way the characters find a way to survive - fair enough that their way is through disobedience, pranks, jokes and crass rejection of anything that denotes an "army" way of doing things. You can sense that they're acting this way in response to the senseless horrors they're subjected to. Obviously they're surgeons, and would see injury every day - but for people to be ordered to be doing this to each other, only for them to try and put things right by operating on them - this must really grind away at a person's sense of the military machine they're a part of. So they find outlets in casual sex and poking fun at everything you or I might find sacred. I don't laugh along all that much, but that doesn't mean I'm not on their side, or don't understand why they're doing what they're doing. When they're part of a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, their work must feel like trying to fix horrible damage that their own leaders are senselessly creating for them. If they weren't the way they are - then they'd lose their minds. This is perhaps why the simpler pure comedy of the television series irked Altman, especially when it became much more famous than his film.

I love

MASH most for what it did - the way it elevated so many actors who didn't have a career yet - with Altman surreptitiously hiring them, because studios would never take such a chance. One of these young people is Bud Cort - who would go on to be the lead in Altman's next film,

Brewster McCloud, and find fame in

Harold and Maude. I love the way it opted for realism over "more of the same" from major studios, and it's sheer irreverence. I love the way it kick-started the careers of Donald Sutherland (struggling to build a career on his great role in

Kelly's Heroes), Elliott Gould, Tom Skerritt and Sally Kellerman. I love this film for setting Robert Altman free and allowing him to make films such as

McCabe & Mrs. Miller,

Thieves Like Us,

The Long Goodbye and

Nashville over the ensuing decade, along with other noteworthy and immensely enjoyable gems. It was 1970 and Altman had a period of sustained excellence ahead of him - outrageously great creations that only grow in stature over time. That all started with

MASH (it

really started with

That Cold Day in the Park) and recognition that this "crazy" and rebellious filmmaker had served his nearly two decade apprenticeship and was ready to create works of art - his first a cream pie in the face of authority and rules-based order.