There is a difference between permutation (change as pure variation) and ramification (change that occurs according to an implicate order, a causality with coherence following a universal law or principle of design).

In fiction, especially science fiction, ramification is less a case of external fidelity (i.e., obeying laws of the known universe, and conforming with known facts of history) internal fidelty (i.e., playing by your own explicit rules) and pseudo-fidelity (i.e., implicit indications we infer from from what we see, and don't see compared against what we would expect to see "Were it the case that 'X' were true"). Nevertheless, ramification matters.

If your spaceship has the Omega-13 and would have come in awfully handy as a solution to deadly crises in episodes 4, 7, 12, and 15, it doesn't quite fit when we discover that our plucky crew had this device at their disposal the whole time in episode 21 when it is used as a deus ex machina to cheat death. Star Trek TOS was notorious for this sort of thing. Mastering a universe-changing technology one week and then forgetting about it the next (e.g., time-travel, telekinesis, psychokinesis, super-speed in human movement, super-speed for the ship).

Another area where this occurs is in design. Think of the TIE-Fighter from Stars Was. The Twin Ion Engine short-range fighter that serves as fodder for our heroes. It looks like a rubber ball placed between two playing cards, a simple but iconic design. Why do they have those two vertical planes? Why does the Millennium Falcon has an asymmetrically placed cockpit? Who knows? It looks cool. It's science-fictiony. George Lucas is not here to explain the plumbing of this world, but to take us on a ride (Star Wars goes to hell when it start explaining). So far, so good. But then we have a problem. Our villain is going to dog fight our hero, so we need him to have a signature bad-guy ship. No worries. He's the boss, so his ride should be a little pimped, right? He can afford the best of the best where is underlings get MilSpec/standard issue stuff. Cool. Let's uhm make his wings longer and give them two bends so that they stand out a bit? maybe give his ship a longer bit on the back end. No worries. In the next movie we have the Falcon hiding in a cave being bombarded, so we can have a TIE bomber! We'll add another cylinder/axel thingy in the middle to hold all the bombs and there you go.

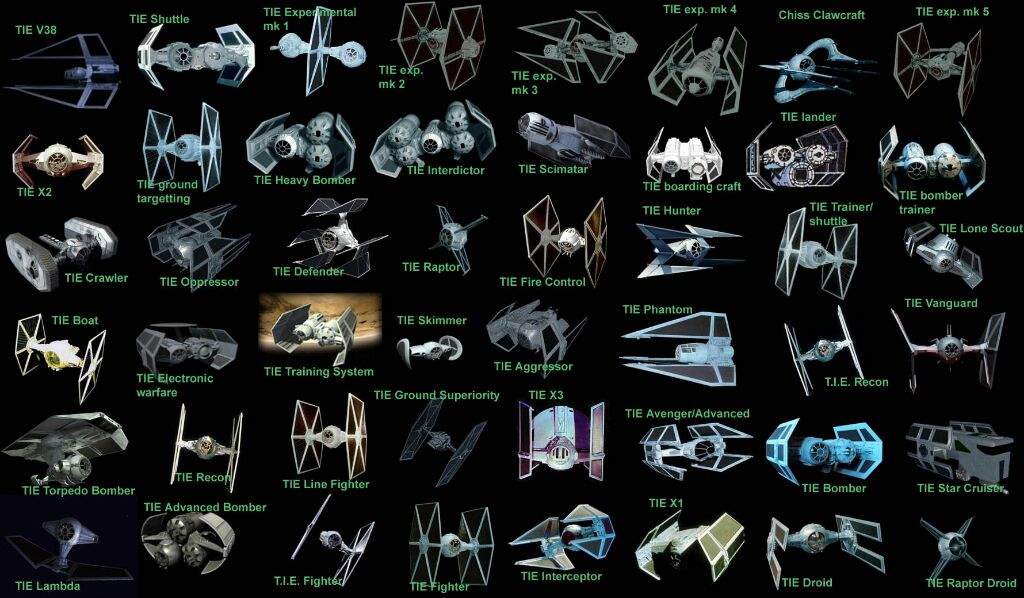

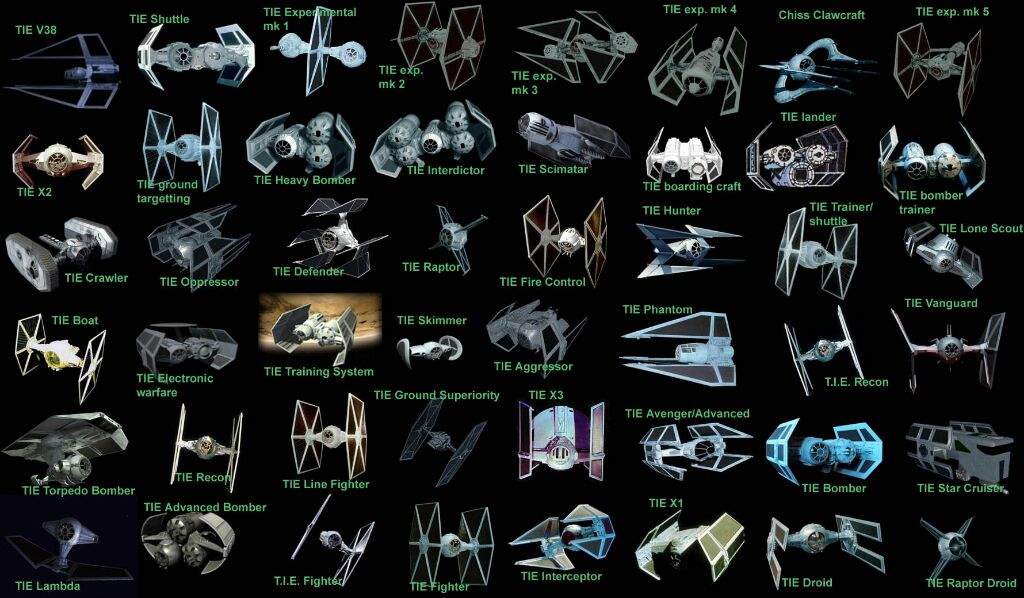

And then madness sets in. We move from ramification to full-on nerd permutation.

We get one wing, three-wing, four wing, etc. The TIE fighter goes from a quirky iconic design to a capricious Brundle-Fly assortment of black-paneled wings and spheres. In the original film, we could imagine some implicate order responsible for the arrangement. The kit-bashers, however, undo any sense anything really needed to have any sort of arrangement. The design is arbitrary. And, of course, in the real world, it is. These aren't real ships. However, our suspension of disbelief requires that we lulled into thinking that there is a "there" there--a world with concerns about optimality and purpose resulting in design rules.

Of course, in the real world we also have an arrangement of aircraft (e.g., delta-wing, swing-wing, straight wing, rotating wings, laminar flow wings, flying tails), so diversity in design is no proof of higglety-piggledy permutation. A swing-wing F-111 Aardvark doesn't have swing-wings because they look cool, but because engineers faced a design problem of optimizing aerodynamics as subsonic and supersonic speeds. Helicopters have spinny-wings not because they look cool, but because this allows them to hover. And so on. And so on. In these cases, however, we still see a unity of design driven by the laws of aerodynamics.

Moreover, a lack of variation in a universe is also something that can throw us out of a narrative. Robot Chicken mocks this quite effectively

In Star Trek, for example, we have the embarrassment of Romulans flying Klingon D-7 cruisers in The Balance of Terror simply because of the limitations of the prop department.

Thus, we can make mistakes in either direction. Thus the question is one of balance (e.g., how much diversity is plausible in a given industry or ecosystem?). If no one ever sparked a light saber again in the prequels we would have been disappointed. And yet there was also something disappointing about the number and colors that appeared in Attack of the Clones in the bug colosseum. The light saber went from a cool (because scarce) weapon color coded between good and evil to a dime-a-dozen bag of skittles in every random color. SLJ wants purple? OK. Want a dark saber? Sure, let's do a dark saber. Somewhere we turned from chivalric techno-knights to jangling keys over the crib.

The slogan of Star Trek is IDIC, but that makes for design chaos. No, let's not do every random assortment of saucers and cylinders imaginable. Rather, let's imagine a universe with design principles driven by engineering necessities. As with almost all things, our question is one of bringing balance to force of design language.

In fiction, especially science fiction, ramification is less a case of external fidelity (i.e., obeying laws of the known universe, and conforming with known facts of history) internal fidelty (i.e., playing by your own explicit rules) and pseudo-fidelity (i.e., implicit indications we infer from from what we see, and don't see compared against what we would expect to see "Were it the case that 'X' were true"). Nevertheless, ramification matters.

If your spaceship has the Omega-13 and would have come in awfully handy as a solution to deadly crises in episodes 4, 7, 12, and 15, it doesn't quite fit when we discover that our plucky crew had this device at their disposal the whole time in episode 21 when it is used as a deus ex machina to cheat death. Star Trek TOS was notorious for this sort of thing. Mastering a universe-changing technology one week and then forgetting about it the next (e.g., time-travel, telekinesis, psychokinesis, super-speed in human movement, super-speed for the ship).

Another area where this occurs is in design. Think of the TIE-Fighter from Stars Was. The Twin Ion Engine short-range fighter that serves as fodder for our heroes. It looks like a rubber ball placed between two playing cards, a simple but iconic design. Why do they have those two vertical planes? Why does the Millennium Falcon has an asymmetrically placed cockpit? Who knows? It looks cool. It's science-fictiony. George Lucas is not here to explain the plumbing of this world, but to take us on a ride (Star Wars goes to hell when it start explaining). So far, so good. But then we have a problem. Our villain is going to dog fight our hero, so we need him to have a signature bad-guy ship. No worries. He's the boss, so his ride should be a little pimped, right? He can afford the best of the best where is underlings get MilSpec/standard issue stuff. Cool. Let's uhm make his wings longer and give them two bends so that they stand out a bit? maybe give his ship a longer bit on the back end. No worries. In the next movie we have the Falcon hiding in a cave being bombarded, so we can have a TIE bomber! We'll add another cylinder/axel thingy in the middle to hold all the bombs and there you go.

And then madness sets in. We move from ramification to full-on nerd permutation.

We get one wing, three-wing, four wing, etc. The TIE fighter goes from a quirky iconic design to a capricious Brundle-Fly assortment of black-paneled wings and spheres. In the original film, we could imagine some implicate order responsible for the arrangement. The kit-bashers, however, undo any sense anything really needed to have any sort of arrangement. The design is arbitrary. And, of course, in the real world, it is. These aren't real ships. However, our suspension of disbelief requires that we lulled into thinking that there is a "there" there--a world with concerns about optimality and purpose resulting in design rules.

Of course, in the real world we also have an arrangement of aircraft (e.g., delta-wing, swing-wing, straight wing, rotating wings, laminar flow wings, flying tails), so diversity in design is no proof of higglety-piggledy permutation. A swing-wing F-111 Aardvark doesn't have swing-wings because they look cool, but because engineers faced a design problem of optimizing aerodynamics as subsonic and supersonic speeds. Helicopters have spinny-wings not because they look cool, but because this allows them to hover. And so on. And so on. In these cases, however, we still see a unity of design driven by the laws of aerodynamics.

Moreover, a lack of variation in a universe is also something that can throw us out of a narrative. Robot Chicken mocks this quite effectively

In Star Trek, for example, we have the embarrassment of Romulans flying Klingon D-7 cruisers in The Balance of Terror simply because of the limitations of the prop department.

Thus, we can make mistakes in either direction. Thus the question is one of balance (e.g., how much diversity is plausible in a given industry or ecosystem?). If no one ever sparked a light saber again in the prequels we would have been disappointed. And yet there was also something disappointing about the number and colors that appeared in Attack of the Clones in the bug colosseum. The light saber went from a cool (because scarce) weapon color coded between good and evil to a dime-a-dozen bag of skittles in every random color. SLJ wants purple? OK. Want a dark saber? Sure, let's do a dark saber. Somewhere we turned from chivalric techno-knights to jangling keys over the crib.

The slogan of Star Trek is IDIC, but that makes for design chaos. No, let's not do every random assortment of saucers and cylinders imaginable. Rather, let's imagine a universe with design principles driven by engineering necessities. As with almost all things, our question is one of bringing balance to force of design language.