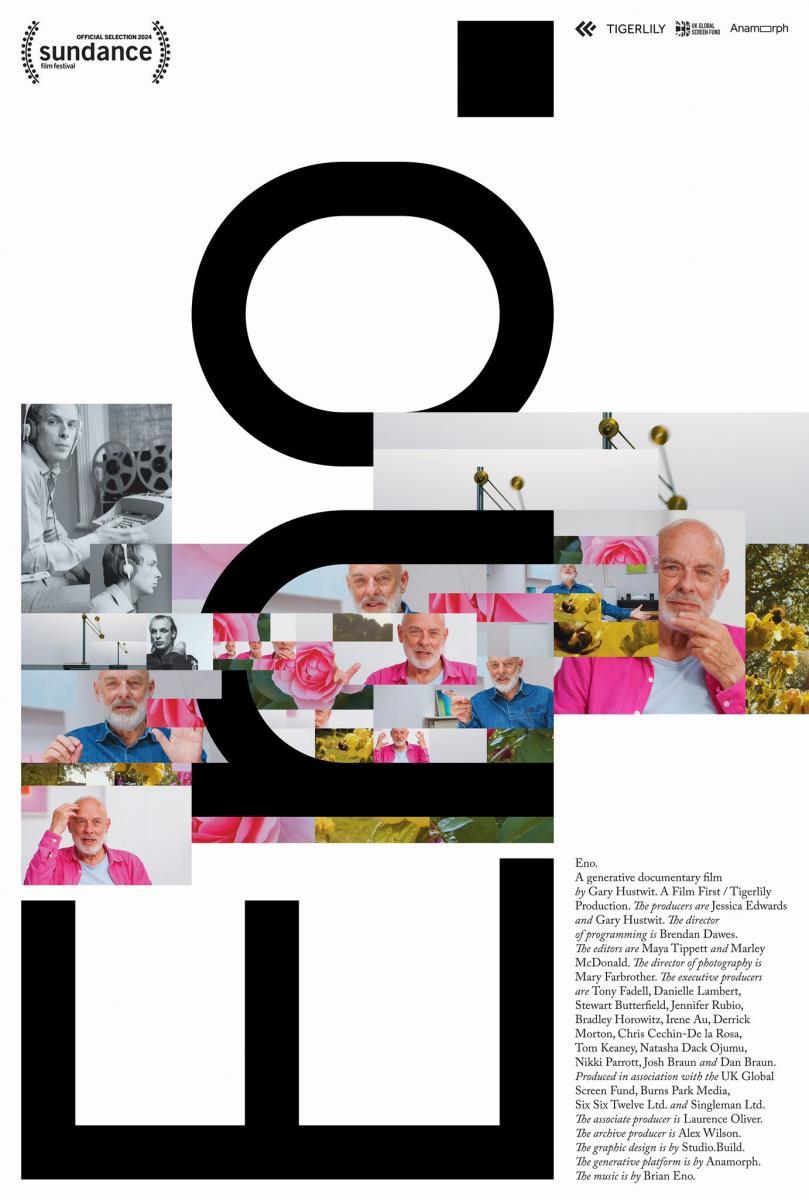

Have you heard about the documentary called Eno?

What is really interesting about the documentary is that there isn't a single version of it, or even a special director's edition or something like that.

There are actually 52 quintillion different versions of the documentary, and you may never be able to watch the exact same version more than once (52 quintillion is 52 billion billion).

Here is a review that explains this a bit more extensively:

What is really interesting about the documentary is that there isn't a single version of it, or even a special director's edition or something like that.

There are actually 52 quintillion different versions of the documentary, and you may never be able to watch the exact same version more than once (52 quintillion is 52 billion billion).

Here is a review that explains this a bit more extensively:

The key to “Eno” comes near the beginning of the film — at least, the beginning of the first version I saw. The musician Brian Eno, the documentary’s subject, notes that the fun of the kind of art he makes is that it’s a two-way street. “The audience’s brain does the cooking and keeps seeing relationships,” he says.

Most movies are made up of juxtapositions of scenes, carefully selected and designed by the editor. But “Eno,” directed by Gary Hustwit, turns that convention on its head. Writ large, it’s a meditation on creativity. But every version of the movie you see is different, generated by a set of rules that dictate some things about the film, while leaving others to chance. (I’ve seen it twice, and maybe half the same material appeared across both films.)

Eno, one of the most innovative and celebrated musicians and producers of his generation, has fiddled with randomness in his musical practice for decades, often propelled along by new technologies. He agreed to participate in “Eno” only if it, too, could be an example of what he and others have long called generative art.

The word “generative” has become associated with artificial intelligence, but that’s not what’s going on with “Eno.” Instead, the film runs on a code-based decision tree that forks every so often in a new path, created for software named Brain One (an anagram for Brian Eno). Brain One, programmed by the artist Brendan Dawes, generates a new version of the film on the fly every time the algorithm is run. Dawes’s system selects from a database of 30 hours of new interviews with Eno and 500 hours of film from his personal archive and, following a system of rules set down by the filmmakers with code, creating a new film. According to the filmmakers, there are 52 quintillion (that is, 52 billion billion) possible combinations, which means the chances of Brain One generating two exact copies of “Eno” are so small as to be functionally zero.

This method is unusual, even unique, among feature-length films. Movies are linear media, designed to begin at the beginning and proceed in an orderly, predictable fashion until the end. The same footage appears in the same order every time you watch.

But “Eno” is set up differently, tapping into an over 60-year tradition of “generative art” of which Eno himself is part. Artists have been working with computers and code-based systems for as long as computers have existed. Early practitioners such as Georg Nees, Frieder Nake and Vera Molnar began exhibiting generative work in the 1950s and ’60s, when A.I. was still just science fiction; they’ve been getting long-overdue attention in recent years with major museum shows at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Centre Pompidou, the Whitney Museum of American Art and an upcoming survey at the Tate Modern this fall.

The idea is relatively simple: The artists work with code as their medium, writing programs that draw, design, play or otherwise create art. (Eno’s outputs are primarily musical.) The key is that the code explicitly invites randomness into the process, which means the work is distinct virtually every time it’s run.

This is different from generative artificial intelligence, though they share some basic frameworks in common. To grossly oversimplify, generative A.I. (think ChatGPT or Midjourney) is trained on existing works, which can then be prompted to produce outputs that are, by definition, derivative of those existing works. So unless the artist builds their own A.I. model, they aren’t working with code. Code-based generative art, on the other hand, uses rules written by a human to make something new. (Some have called it post-conceptual, following artists like Sol LeWitt; it can help to think of it in that lineage.)

The version of “Eno” that toured the film festival circuit was sometimes generated on the fly by Brain One. (I don’t know how this will work when, and if, the film becomes available for home viewing, but I’m sure it will be interesting.) That’s expensive, technically tricky and difficult to manage, so the version of the film you’ll see will likely have been created in advance by Brain One — you’re not watching an algorithm make selections as you’re watching it, just the final product.

No matter. Rather than getting hung up on the technology itself, it’s worth thinking about how it works on us. The effectiveness of a generative artwork has a lot to do with the medium of its output. A single still image, for instance, affects us differently from a song, and they’re both different from a movie. That’s where Eno’s idea about the human brain “cooking” comes in. The meaning in a movie, a time-based medium, resides both in what happens onscreen and what your brain fills in about the rest. That’s why filmmakers so doggedly cut and recut their movies; they want to make sure that the audience experiences mood and character and themes and rhythm the way they intended. “Eno” contains some fixed edits, with sequences that were created and cut together by Hustwit and his team. But the sequences that are selected and the order in which they appear change from version to version, and there are short, montage-like segments that clearly select from among a library of tiny clips.

All of this drives at the movie’s meaning itself, which is a little hard to pin down by design. One might say it’s embedded even more than usual in the form, rather than the content. Only one version I saw included a discussion of Eno’s composition of the Microsoft Windows theme jingle, for instance; another one included discussion of his work with the band Devo. But both versions included some overlapping sections, including lots of contemporary interview footage shot by Hustwit, a scene in which Eno shows YouTube clips of music that shaped him, and an unforgettable archival sequence from 1984, in which U2 writes “Pride (In the Name of Love).”

Yet the two versions seemed to be fundamentally different movies. In the first version I saw, much of the discussion explored the way that pop musicians such as Eno and many of his collaborators — like David Bowie and Talking Heads — create and project an identity when they perform, making that persona part of their medium. In essence, it became a film “about” art and identity. Another version focused more on the role of pushing boundaries and trying arbitrary experiments (like those encoded in Eno’s deck of “Oblique Strategies”); it was a documentary “about” the messy process of creativity.

Those meanings were generated by my mind, not the movie itself; putting a whole new set of scenes together might give me another meaning. Which makes the whole thing more clear: To the extent “Eno” has a single, fixed meaning, it’s about how we, the audience, understand the world around us. Our brains seek out patterns and assign sense where there is none, and thus we become creators with the artist. In the past, postmodern artists and authors sought to remove the author from the equation, leaving the burden of creation on the audience to the extent it was possible.

“Eno” tries to find some kind of balance in the middle, inviting us to sense the patterns ourselves. And the results are both marvelously watchable — you wouldn’t know all this complicated generative stuff was even happening if you went in cold — and inspiring. There’s a pure joy to this documentary, a sense that creativity is miraculous and we ought to be grateful that we get to participate in it. I left both screenings full of ideas for my own work.

That’s not to say that I want to see the world flooded with generative movies; I prefer most films to be the same, no matter who’s watching them. We learn so much about one another, and ourselves, from discovering how we watch and think about the same movie. But the generative framework makes perfect sense for “Eno,” a documentary about a man who’s spent his career rewriting the rules of the possible — not just finding a new way to say something, but changing the act of saying itself.

Most movies are made up of juxtapositions of scenes, carefully selected and designed by the editor. But “Eno,” directed by Gary Hustwit, turns that convention on its head. Writ large, it’s a meditation on creativity. But every version of the movie you see is different, generated by a set of rules that dictate some things about the film, while leaving others to chance. (I’ve seen it twice, and maybe half the same material appeared across both films.)

Eno, one of the most innovative and celebrated musicians and producers of his generation, has fiddled with randomness in his musical practice for decades, often propelled along by new technologies. He agreed to participate in “Eno” only if it, too, could be an example of what he and others have long called generative art.

The word “generative” has become associated with artificial intelligence, but that’s not what’s going on with “Eno.” Instead, the film runs on a code-based decision tree that forks every so often in a new path, created for software named Brain One (an anagram for Brian Eno). Brain One, programmed by the artist Brendan Dawes, generates a new version of the film on the fly every time the algorithm is run. Dawes’s system selects from a database of 30 hours of new interviews with Eno and 500 hours of film from his personal archive and, following a system of rules set down by the filmmakers with code, creating a new film. According to the filmmakers, there are 52 quintillion (that is, 52 billion billion) possible combinations, which means the chances of Brain One generating two exact copies of “Eno” are so small as to be functionally zero.

This method is unusual, even unique, among feature-length films. Movies are linear media, designed to begin at the beginning and proceed in an orderly, predictable fashion until the end. The same footage appears in the same order every time you watch.

But “Eno” is set up differently, tapping into an over 60-year tradition of “generative art” of which Eno himself is part. Artists have been working with computers and code-based systems for as long as computers have existed. Early practitioners such as Georg Nees, Frieder Nake and Vera Molnar began exhibiting generative work in the 1950s and ’60s, when A.I. was still just science fiction; they’ve been getting long-overdue attention in recent years with major museum shows at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Centre Pompidou, the Whitney Museum of American Art and an upcoming survey at the Tate Modern this fall.

The idea is relatively simple: The artists work with code as their medium, writing programs that draw, design, play or otherwise create art. (Eno’s outputs are primarily musical.) The key is that the code explicitly invites randomness into the process, which means the work is distinct virtually every time it’s run.

This is different from generative artificial intelligence, though they share some basic frameworks in common. To grossly oversimplify, generative A.I. (think ChatGPT or Midjourney) is trained on existing works, which can then be prompted to produce outputs that are, by definition, derivative of those existing works. So unless the artist builds their own A.I. model, they aren’t working with code. Code-based generative art, on the other hand, uses rules written by a human to make something new. (Some have called it post-conceptual, following artists like Sol LeWitt; it can help to think of it in that lineage.)

The version of “Eno” that toured the film festival circuit was sometimes generated on the fly by Brain One. (I don’t know how this will work when, and if, the film becomes available for home viewing, but I’m sure it will be interesting.) That’s expensive, technically tricky and difficult to manage, so the version of the film you’ll see will likely have been created in advance by Brain One — you’re not watching an algorithm make selections as you’re watching it, just the final product.

No matter. Rather than getting hung up on the technology itself, it’s worth thinking about how it works on us. The effectiveness of a generative artwork has a lot to do with the medium of its output. A single still image, for instance, affects us differently from a song, and they’re both different from a movie. That’s where Eno’s idea about the human brain “cooking” comes in. The meaning in a movie, a time-based medium, resides both in what happens onscreen and what your brain fills in about the rest. That’s why filmmakers so doggedly cut and recut their movies; they want to make sure that the audience experiences mood and character and themes and rhythm the way they intended. “Eno” contains some fixed edits, with sequences that were created and cut together by Hustwit and his team. But the sequences that are selected and the order in which they appear change from version to version, and there are short, montage-like segments that clearly select from among a library of tiny clips.

All of this drives at the movie’s meaning itself, which is a little hard to pin down by design. One might say it’s embedded even more than usual in the form, rather than the content. Only one version I saw included a discussion of Eno’s composition of the Microsoft Windows theme jingle, for instance; another one included discussion of his work with the band Devo. But both versions included some overlapping sections, including lots of contemporary interview footage shot by Hustwit, a scene in which Eno shows YouTube clips of music that shaped him, and an unforgettable archival sequence from 1984, in which U2 writes “Pride (In the Name of Love).”

Yet the two versions seemed to be fundamentally different movies. In the first version I saw, much of the discussion explored the way that pop musicians such as Eno and many of his collaborators — like David Bowie and Talking Heads — create and project an identity when they perform, making that persona part of their medium. In essence, it became a film “about” art and identity. Another version focused more on the role of pushing boundaries and trying arbitrary experiments (like those encoded in Eno’s deck of “Oblique Strategies”); it was a documentary “about” the messy process of creativity.

Those meanings were generated by my mind, not the movie itself; putting a whole new set of scenes together might give me another meaning. Which makes the whole thing more clear: To the extent “Eno” has a single, fixed meaning, it’s about how we, the audience, understand the world around us. Our brains seek out patterns and assign sense where there is none, and thus we become creators with the artist. In the past, postmodern artists and authors sought to remove the author from the equation, leaving the burden of creation on the audience to the extent it was possible.

“Eno” tries to find some kind of balance in the middle, inviting us to sense the patterns ourselves. And the results are both marvelously watchable — you wouldn’t know all this complicated generative stuff was even happening if you went in cold — and inspiring. There’s a pure joy to this documentary, a sense that creativity is miraculous and we ought to be grateful that we get to participate in it. I left both screenings full of ideas for my own work.

That’s not to say that I want to see the world flooded with generative movies; I prefer most films to be the same, no matter who’s watching them. We learn so much about one another, and ourselves, from discovering how we watch and think about the same movie. But the generative framework makes perfect sense for “Eno,” a documentary about a man who’s spent his career rewriting the rules of the possible — not just finding a new way to say something, but changing the act of saying itself.