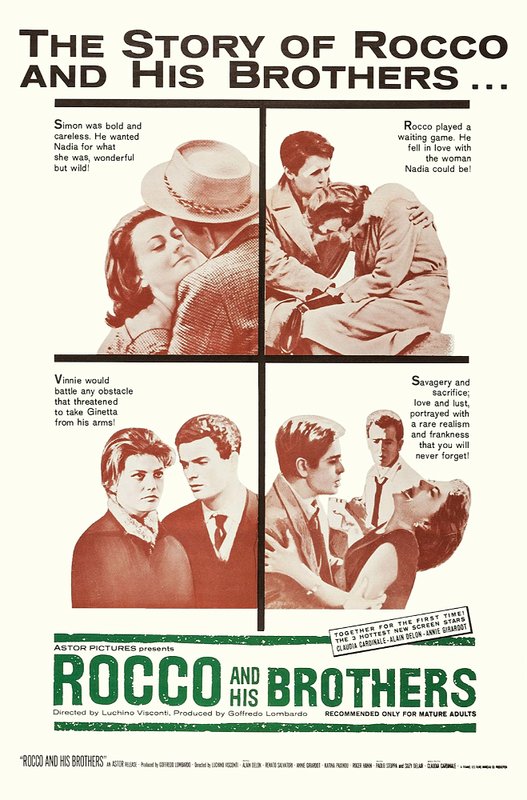

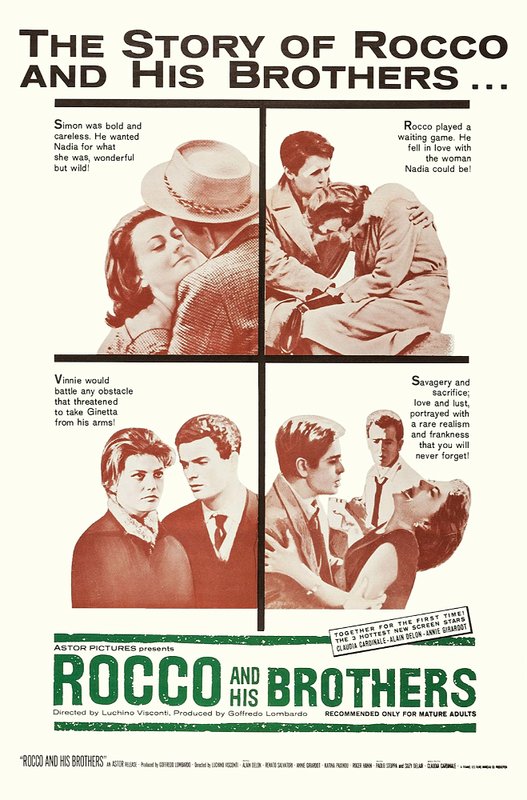

Rocco and His Brothers (Rocco e i suoi fratelli) - 1960

Directed by Luchino Visconti

Written by Suso Cecchi D'Amico, Pasquale Festa Campanile, Massimo Franciosa, Enrico Medioli & Luchino Visconti

Starring Alain Delon, Renato Salvatori, Annie Girardot, Katina Paxinou, Roger Hanin & Spiros Focás

A move from the country to the city has long stood for a loss of innocence in literature and film - urban decay, ruthless industrialization and rootless anonymity immediately come to mind when we see visions of cold, grey concrete and artless tenements. In Luchino Visconti's

Rocco and His Brothers it's the Parondi family who are making the journey from their rural home to the city of Milan - the father of Rocco (Alain Delon), Simone (Renato Salvatori), Ciro (Max Cartier), Luca (Rocco Vidolazzi) and Vincenzo (Spiros Focás) having died, leaving their mother, Rosaria Parondi (Katina Paxinou) a widow. Vincenzo is already there, engaged to be married to Ginetta (Claudia Cardinale - in one of her early film roles), but the Parondi's are spurned by his fiance's family and have to take up residence in a squalid basement. The outgoing tearaway of the group, Simone, takes up boxing and falls in love with prostitute Nadia (Annie Girardot), and in the process begins to steal, drink and otherwise cause trouble for himself. When Rocco follows suit, both in profession and later, during his military service, choice of lover, it creates a rift that has flow-on effects which threaten to tear the very fabric of the close-knit family apart, and it's this most generous and magnanimous of the Parondi brothers who decides he must give his all to save Simone and the bond his brothers share.

Rocco and his Brothers is a heavy, serious film - never miserable, and never really joyous and full of wonder, but measured and thorough in it's examination of familial bonds and how they can be slowly fractured and worn down by both the failures and the successes of a family's individual members. To do this it separates itself into individual segments labeled with each brother's name, giving us a chance to see the whole situation from each different point of view. Rocco and Simone fight - quite literally, as they both take up a career in boxing with differing degrees of success. They are the yin and yang of this family, and really dominate the film as a whole - so much so that I wouldn't have thought twice if the movie had of been called

Rocco, and his Brother Simone, although Nadia does have a major role to play in the drama, and if anything is a tragic victim of the dynamics at play here. From what I've seen of his work so far, Luchino Visconti is one for a particularly serious and searching drama without any messing around or idle play. He doesn't soak the screen in melodrama or excess, but studies his way through and helps us to see a bigger picture that has more wisdom behind it than grandiosity or the heartrending magic of neorealism.

Most films that had Alain Delon featuring in them benefited from his presence, and this one is no exception. I don't know what kind of lightweight division he was boxing in - I could never quite see him as such a fighter (that handsome face!) - but he does have the aura of success about him that his character needed, not to mention a sense of misguided nobility and sense of purpose in protecting his brother. He reflects pain quite well, but is even surpassed in this respect by Renato Salvatori, whose anguish and torment burns up the screen and creates all kinds of angst for the audience whenever his character is doing something terrible (to every single person who has the misfortune to know him.) I thought Annie Girardot was also quite good as Nadia - the street-smart, experienced one when the boys first arrive in town who can't, however, avoid becoming a victim of circumstance after meeting Rocco after a stint in jail and actually falling for him. I hate to use the phrase "collateral damage" when talking about a person, but she does seem to take the brunt of what turns out to be the worst kind of sibling rivalry. Both Girardot and Katina Paxinou get a chance to show the audience their character's intense emotional pain.

Visually we get to experience a lot of real texture by being on location and seeing so much happen in the streets and on the sidewalks of Milan - with scenes on bridges, in parks and on the move as the entire Parondi family moves house in a manner that directly reminds us of refugees on the move during wartime. They carry their belongings on a cart and trundle as a tightknit lot along their way as regular city dwellers sigh and basically look upon them as foreigners. I love a film that makes good use of locations and doesn't stick to moribund studios - no matter how detailed set decorators try to lull us into a sense of reality. The film's score is one to seriously listen to at high volume while reclining with your eyes closed - sans movie. It's something exceptional from Nino Rota, and very worthy of the term "operatic", with it's range and vibrant, melodic delightfulness. Yes, there are moments or two where I think it's just about to segue into the

Godfather theme - it very nearly gets there at times - but I thought it was one of the finest technical aspects to the film and a big winner for me personally. It gives the movie a grand, larger than life atmosphere to soak in and a sense of how operatic and tragic the story will become.

In the screenplay, much is made of the Parondi's move from their rustic country home in Italy's south to Milan, and the brothers often find themselves talking wistfully of going back one day - it's almost as if they're talking about their already lost youth - and desire to have that back. In fact the film ends with such a conversation - in the family's desperate attempts to escape poverty and build a more fruitful kind of existence during Italy's "economic miracle" - the boom of 1958 to 1963 - they've left something behind that all the brothers yearn for. It's as if a Faustian bargain has been struck, with the search for the financial benefits of their new location being paid for with the disintegration of the family. I thought it was interesting that Ciro both holds out hope that the youngest of the clan, Luca, will both be able to go back home one day and live a better life, but also tells him that by that time thier home town itself will have changed - transformed by a changing world that will benefit the next generation. I must admit I was surprised by that note of optimism, but it was interesting to see this tragedy as not indicative of a general degradation of society but instead a kind of by-product of a evolving, advancing world - even if it's changing for the better. There are casualties when migration occurs - winners and losers always.

One last point of interest before I finish - I was also fascinated by being presented with a saintly character - Rocco - who does a great disservice to his brother Simone and his family by trying to martyr himself for his benefit. If Simone accrues ridiculously-sized debts, Rocco will put aside 10 years of his life to pay them off. If Simone loves Nadia, Rocco will insist Simone have her - despite how Nadia and Rocco feel about each other, or even Nadia's own wellbeing. If Simone is in big trouble with the law, Rocco will hide him and won't judge him. Of course, all this does is encourage and allow Simone to fall deeper and deeper into the dark pit he's already lost in. It doesn't matter if Simone spits on Rocco or even hates him. It's what we popularly refer to nowadays as "enabling", and it's what a lot of parents do for their kids - despite the fact that it's a recipe for much worse trouble down the road. Rocco's sense of brotherhood and family becomes a tightly-defined principle that knows no bounds and can withstand any personal injury. Rocco and Simone are mirror images of each other - a success and a failure who both seem completely cut adrift from what we feel regarding the other brothers - wellness and contentment with their new lot in life. There's no going back home for them.

I liked

Rocco and His Brothers - I didn't necessarily like the way many of the characters in it behaved, or the way Nadia managed to draw the short straw in a society and time more in favour of what a man might make a woman submit to. Simone was a particularly ugly, brutish man that I hated a great deal - he had just about every bad trait a human being can have, and it was by that route that I lost any and all favourable feelings I had for Rocco when he put family above all else - even common decency and morality. The film feels very weighty and heavy - anybody who watches any mainstream drama or popular, contemporary films would find a great deal of contrast when comparing them to

Rocco and His Brothers, where every scene feels like it could be analysed and talked about - these people are short on small talk for the most part, and the emotional intensity of all their interactions added together gives the movie a depth that makes it as weighty as it is. You get your money's worth with a Visconti film - he made them with a great deal of careful forethought and an enormous amount of purpose. Fascinating to see how he'd evolved when it came time for Italy's newfound economic power and the way it was changing the world as he saw it.