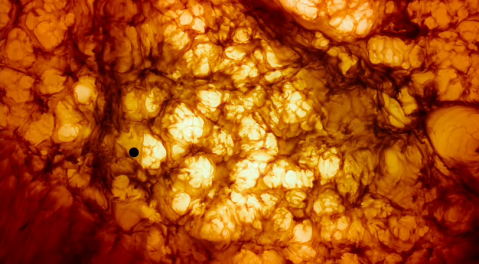

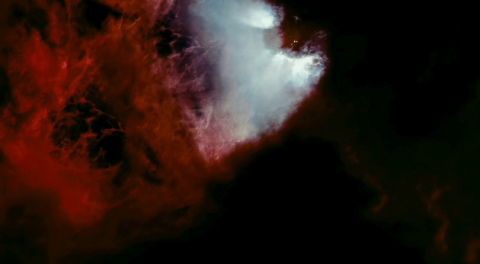

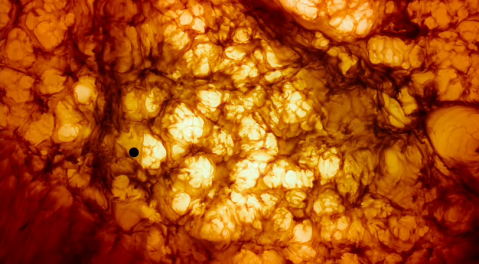

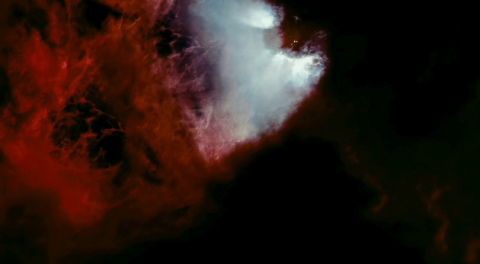

Two main controversies surround

The Tree of Life. First is the daring inclusion of a largely autonomous VFX sequence depicting the birth of the universe, the coagulation of the solar system, the evolution of life on Earth up to the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction, and a brief bookend presaging Earth’s annihilation. Second is the inclusion of a heavily symbolic finale sequence—reminiscent of the coalescence of dream and memory in

8½—which finds scattered precedents towards the beginning of the film and delimits the creation sequence. Both mark entirely new territory for Malick. Whereas his previous films seemed mired in the pure, unfettered presentation of a self-enclosed, human-disclosed world, here Malick takes us beyond the option of worldhood in two temporal directions: both the ancestral and the terminal. For the first time Malick explores the radical contingency of the material universe in the utter absence of any Dasein whatsoever. It is also the first time that, as far as my interpretation will go, Malick attempts to actually

picture the scene of Dasein in its primacy as a concept.

Creation Sequence: a Materialist Reading of Job

It is a wonder that such a scientifically-revealed depiction of creation has taken so long to be integrated into a work of mainstream art, for the technological capability enabling such a depiction has existed for more than a decade. Yet, despite its obviousness, Malick’s bid for its inclusion remains audacious precisely because of its apparent incongruity with the bulk of the film. Though certainly less transparently incorporated into the momentum of an overall narrative, Malick’s move clearly parallels Kubrick’s own prehistoric and cosmic reflections in

2001 and induces much of the same effect (quite possibly, even, for the same goals). What remains unclear is which juxtaposition comes off as more jarring; is it Kubrick’s, with two essentially

alien worlds, or is it Malick’s, with worlds both alien and intimate, casually intermixed?

Still, this distinction plays mostly with the intellect. When one takes either Kubrick’s or Malick’s work as a whole, nothing really seems out of place. After time and repeated examination, it slowly becomes clear that—far from being ancillary to what some might see as the true “substance” of the film—these staggering displays of visual splendor are not only crucial to the film’s meaning but also crucially placed.

Consider the film’s opening idea—recalling the passage when God asks Job, “where were you when I laid the Earth’s foundation . . . while the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?” (Job 38:4-7)—in relation to Malick’s decision to introduce the human element of the film with a shattering, irrational tragedy; that is, the very kind of experience that characterizes Job’s own frustration with God. We find in these opening scenes a distraught Mrs. O’Brien (Jessica Chastain) asking herself the very same questions that plagued Job. She then starts to receive a slew inadequate condolence from her neighbors like Job does from Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar. None of these answers seem to satisfy her as none satisfied Job.

What else then is the subsequent interpretation of the natural creation of the universe but that of God Himself coming “out of the whirlwind” (Job 38:1), speaking to Job of His indifference to the petition of mortals, His utter transcendence beyond their understanding, and the insolence of any man who dares to explain away His motives so easily? After showing the O’Briens’ grief at the inexplicable, Malick immediately answers their pain in the most direct and powerful way possible. Malick provides us, the audience, with the very same answer that God provides Job, or rather, the authors of the Bible provides their readers. Our lives are just a sliver of the life of God, or—in a secular sense much more appropriate to Malick’s Heideggerianism—our lives are just as violently contingent as the deep history that precedes us and, as shown later on in the film, the vast future ahead.

Only by retelling the Book of Job in the most honest, materialist way possible can Malick then go on to focus the rest of the film in a worldly or human-meaningful frame. Within the span of a third of the film, Malick situates the entirety of humanity’s existence into a single point within the unfathomable stretches of cosmic time from whence everything we know or will ever know became what it is and will continue to become. Even before his affectionate examination of a particular Dasein through the O’Briens and his figurative portrayal of Dasein’s communal universality through the movement of love—that is, the beach finale—Malick first seeks to humble us, to put us in our place. Not, as Christianity might have it, in a misanthropic way, but through a simple contrast of space and time. We

are small and we

are brief, he says with these first chapters:

do not presume you can understand it all. It is only afterwards that he at last allows us to revel in the beauty of this smallness and brevity in the only sense it bares significance to Dasein.

Finale Sequence: the Fourfold Root

Even on a purely aesthetic level, the finale sequence of

The Tree of Life is difficult to reconcile with the rest of Malick’s otherwise remarkable oeuvre. Especially in relation to the breathtaking grandeur of the majority of

The Tree of Life alone, its ending comes off as plain and sometimes even a little silly. If taken as separate works, these nebulous montages—the elder Jack’s (Sean Penn) syncopated journey through multiple desert landscapes, the fully submerged bedroom with a boy swimming through it, Mrs. O’Brien’s radiant reconciliation with God in the presence of several mysterious young ladies, the convergence of Jack’s human relationships both past and present on a beach at sunset—could have called great significance to their own craftsmanship, spiritual affects, and melodic continuity, but here they must take on duties far above a mere aesthetic presentation. Here, they must

live up to their subsuming creation.

No one would claim it an easy task to imagine an alternative conclusion tothis filmor, for that matter, to even state the appropriate end

point to a Malick film, let alone

how this should be offered. It is by their pre-reflective, stream-of-consciousness natures that Malick’s films often seem capable of finding conclusion at any number of moments past, say, their midpoint. It all comes off as being extremely dependent on just what he is interested in exploring or how far he is willing to go—how far he is willing to take us. Yet, it is precisely because of this uncertain endpoint that Malick’s audience will ultimately attach so much more import to his specific choices than to a more conventional cinema. And, since

The Tree of Life displays Malick’s most liberated form to date, his decisions surrounding its conclusion have carried all that much more weight as crucial to an overall judgment of the already-nebulous (no pun intended) film as a whole; that is, even if the film’s coda is just a semblance of a thought, its consequence proportional to its running time.

We can return to Malick’s earlier films for signs of precedent. Most relevant is his serene

Days of Heaven (1978) and its spatial simplicity of wide, open fields with tiny figures striding upon it. Structurally, this mirrorsthe desert and beach geographies of

The Tree of Life‘s finale. Certain location choices for

The Thin Red Line also suggest this minimalism. When presented mostly with landscapes arranged like geometric planes and humans as points upon those planes, there already begins to emerge a sense of ontological abstraction. Indeed, correspondences abound between Malick’s spacious mise-en-scène and Heidegger’s fourfold of earth, sky, mortals, and divinities.

In stark contrast with today’s popular postmodernist injunctions toward nomadicism and the overthrowing of identity for a being of constant movement and reinvention (which, incidentally, is a position I have tended to sympathize with as of late), Heidegger seeks the redemption of authentic Dasein through certain focal practices exemplified by a deep, familial collectivity. Earth is, in this sense, a set of vital practices that grounds the rest of our daily life on a background of collective understanding. In many ways, we

already experience this understanding or mattering as earth, and there are as many earths as there are contexts for social behavior. Sky then emerges from earth as the set of possible practices built upon or appropriate to the background in question. Although all aspects of the fourfold should be taken relation to us, the mortals, the sky represents our limit as individuals if we are to remain faithful to some identity. Our ability to let go of our identity can then be seen as our ability to die or our mortality.

Divinity manifest itself not necessarily in religious practices but in a moment where the practices of the earth and sky are functioning in a singularly harmonious interplay between creativity and unity. Dreyfus’s example for divinity in his “Highway Bridges and Feasts”—a fantastic exegesis of Heidegger’s attitudes towards technology—is an experience of union such that one is prompted to wish aloud for the participation of others not present. It does not have to be something particularly momentous; it can be as ordinary an experience as a baseball game, though the entire point behind the name is that, when considering all the factors necessary to make such a divinity possible, such a harmony is nothing short of extraordinary: indeed, divine.

Of course, Malick is certainly not the only filmmaker to depict these sort of practices. Sentimentalists like Ford, Capra, and Spielberg love to fill their works with familial displays of divinity. What distinguishes a film like

Days of Heaven or

The Thin Red Line is not at all

what is being told or shown, but rather

how it is done. Malick attempts more than any other filmmaker, either past or present, to display these moments in their very being

as moments and not as detailed stages upon which characters have been mapped. The famously “divine”

Goodfellas sequences do revel in a kind of familial harmony, but Scorcese’s form is simply too deliberately calculated to capture it in its full glory. The viewer is left instead marveling at

Scorcese‘s masterful choreography rather than the primacy of what is being experienced by all the members present in the scene. It is precisely Malick’s extraordinary ability to craft pure presentations of these beautiful materializations of divinities in all of their divinity that singles him out as both the preeminent auteur who is changing the way we understand film and the overly vague, narratively lazy hack that he is occasionally dismissed as.

What then can be said about Jack’s mysterious encounter in lieu of the fourfold? Could the gathering at the beach be something like a portrait of Dasein itself? Considering Malick’s uncharacteristic, first-time inclusion of a series of strictly irreal images, it is not unreasonable to posit this sequence as the film’s entrance into yet another way of seeing; that is, apart from the rest of the film’s already remarkable way. Whereas the previous portions of the film largely match the verisimilitude associated with Malick’s previous works, here we are taken for the first time into a location of pure fiction: the metaphysical scene of Dasein as a concept, visualized and reified.

It is the divine scene of Dasein as a collective being-with-others, the plane of immanence upon which the subjectivity of the subject is constructed, a coalescence of earth and sky, divinities and mortals. Malick shows us a place where the elder Jack is himself just one aspect of his Dasein among many, though not all are equally potent in their manifestation; his parents clearly take the center stage. Always, he says, do they wrestle inside of him.

This is the great genius of Heidegger: the idea that our very subjectivity emerges from the intersubjective interactions of which we are, from birth, forced to take part. What Descartes spells out as the incorrigible subject—the ultimate empirical and ontological abyss: the dark night of the soul—turns out, for Heidegger, to be built upon its very inversion. It is in fact the collective and our socialization into the collective’s earthy, grounding practices that allow us to make sense of the world at all.

There is no more apt image of this immediate thrownness into the world than the child swimming out from an underwater room to witness his birth as if already familiar with its recognizable forms. The home—and all the different kinds of equipment that come with it—is indeed the first place most of us happen to find ourselves as we gain the skills to maintain continuity known as ourselves.

Final Shot: the Bridge

Still, the film’s most interesting connection with the fourfold has yet to be drawn. I am speaking here of the final photographic frame of the film before its dissolve into the mystifying light—a motif mirrored at least once during that film as the reflections of bathwater against a wall—which also began the film. The specific shot in question is of a modern suspension bridge against an orange sky. Again, I defer directly to Heidegger, who has quite a lot to say on bridges. Consider the following passage cited by Dreyfus from Heidegger’s “Building Dwelling Thinking”:

Ever differently the bridge escorts the lingering and hastening ways of men to and fro . . . The bridge gathers, as a passage that crosses, before the divinities–whether we explicitly think of, and visibly give thanks for, their presence, as in the figure of the saint of the bridge, or whether that divine presence is hidden or even pushed aside.

For Heidegger, a bridge is a kind of simple, technological instrument that can provide a starting point for the sorts focal practices described by the fourfold. One notes that, of the relatively little screen time the elder Jack is given outside of his metaphysically impressionist landscapes, most of that time is spent in silent contemplation of the chilly, angular skyscrapers within which he works.

He, like his father before him, designs machines for a living in an environment so sterile that a newly planted tree can prompt a deep reminiscence of his childhood memories, of which we are subsequently so privileged as to witness. This regression is the same longing of the past of Heidegger’s mawkish love for the peasants of the Black Forest. Simply put, it is the longing for divinity; that is, the divinity of the dinner table, of the schoolhouse, of wrestling with brother in the yard, of chasing mother through the house, of acting out with friends . . . Feeling lost among the impersonal world of which he works, Jack longs for these divinities once again, and Malick allows us to experience Jack’s divinities for the first time in relation to our own.

How then might we reunite the shimmering steel of the suspension bridge with a gathering of fourfold if it is also already hopelessly implicated with the technological fortress that Jack seeks to escape? The postmodern world as exemplified through technology is first and foremost one of dispersion and alienation from identity. This seems immediately opposed to the realization of divinity through the fourfold.

Yet, what is the experience of a bridge but one of brief unification in a world utterly divided, specialized, and estranged from its own constituents as they are from each other? A bridge, by practical necessity and economic calculation alone, is rare among the roads and places it connects.

A bridge is always in some sense temporary; no one ever stays on a bridge. One is always traveling over it. The collective, endlessly divergent beforehand, somehow finds a reason to cross that can be embraced across its all of its parts. The postmodern divinity can no longer be found in the harmony of interconnection but the brief unity towards a common goal upon a technological instrument such as a bridge, even if that goal is openness itself.

Addendum: Heidegger contra Descartes

Consider this section as an initiation to Heidegger for the curious. I myself am scarcely initiated, so please, experts, expect and forgive any unwarranted generalities or gross misreadings!

Heidegger is perhaps the most important figure of 20th century continental philosophy, second only to Nietzsche in terms of influence—for whom Heidegger himself owes a great deal. His innovations parallel those of Wittgenstein in Anglo-Saxon circles, and both philosophers can be seen to mark analogous turning points in the progress of their respective philosophical spheres. Instead of Frege/Russell’s “linguistic turn”, Heidegger returned continental philosophy firmly to the question of being qua being, which had not been, he claimed, seriously addressed since antiquity. From the Eleatics onward, it seemed philosophy had been hopelessly enamored in a metaphysics of presence, a metaphysics which had already

assumed too much of being.

The most notable metaphysician of presence is perhaps Descartes himself who famously introduced the ontological split between res cogitans (thinking thing) and res extensa (extended thing). Indeed, it has now become a common tenet of our everyday language to speak of the subjective—whimsically alluded to by Brad Pitt’s character at one point in the film—and the objective, where the object is forever

exterior to the subject and enters into a relationship with the subject only through some

interior representation. We are, for Descartes, utterly cut off from any direct access to what is commonly phrased as “the outside world”—the most that can be expressed between them is a correlation.

What Heidegger has to say here is simple: the subject/object distinction comes in all too late; contrary to Descartes’ apparently fundamental claim of

cogito ergo sum, this distinction still does not begin at the beginning. For Heidegger, ontology is not the naming of irreducible or incontrovertible entities but rather the revelation of the very conditions of possibility for this naming. Any metaphysics of presence then already supervenes upon an even more primordial being, one where humans are not isolated souls looking to the outside world but rather local instantiations of that world always already

in the world. The exceptionality of human existence (what Heidegger calls Dasein)—as opposed to the being of, say, a rock—lays in our unique ability to take a

stance on our own being by rendering intelligible and sensible the world in which we have been embedded through the formation of cultures, language-games or, to bring it back in relation with Descartes, our various

intersubjective practices. Whereas traditional views of ontology simply pass over this vital process of world disclosure

before being-in-the-world, Heidegger’s new conception of ontology is distinctly focused on the latter.